Blackhole Explained: An Essential Guide to Cosmic Singularities

Read about Blackhole Explained: An Essential Guide to Cosmic Singularities on physics

Blackhole Explained: An Essential Guide to Cosmic Singularities

Approximately 100 million stellar-mass black holes are estimated to reside in the Milky Way galaxy alone, a figure highlighted by recent astronomical surveys, revealing the pervasive influence of these enigmatic cosmic entities. Blackholes represent regions of spacetime where gravity is so intense that nothing, not even light, can escape their pull. This comprehensive guide aims to demystify black holes, exploring their formation, diverse types, and the profound effects they have on the fabric of the universe. We'll delve into cutting-edge research and the ongoing quest to understand these ultimate gravitational wells, providing definitive value for anyone fascinated by the cosmos.

Blackhole Basics: What Are They and How Do They Form?

A blackhole begins its life from the catastrophic collapse of a massive star, or through other highly energetic processes in the universe. At its core lies a singularity, a point of infinite density where all the mass of the black hole is concentrated. Surrounding this singularity is the event horizon, often called the 'point of no return.' Once an object crosses this boundary, it is irrevocably drawn into the black hole, unable to escape its gravitational grasp.

Stellar-mass black holes, the most common type, form when a star roughly 20 times more massive than our Sun exhausts its nuclear fuel. Without the outward pressure from fusion to counteract gravity, the star's core collapses inward, triggering a supernova explosion that blasts away the outer layers. What remains is a super-dense core that continues to collapse into a black hole.

Supermassive black holes, on the other hand, are millions to billions of times the mass of the Sun and are believed to reside at the centers of nearly all large galaxies, including our own Milky Way. Their formation mechanisms are still debated but likely involve the accretion of vast amounts of gas and dust over billions of years, or the mergers of smaller black holes.

Key Takeaway: A blackhole is a region of spacetime with gravity so strong that nothing can escape, defined by its singularity and event horizon. They form from massive stellar collapse or through gradual accretion in galactic centers.

Unveiling the Cosmos: Types of Black Holes and Their Unique Traits

While all black holes share the fundamental characteristic of inescapable gravity, they come in several distinct types, each with unique origins and properties. Understanding these variations is crucial for comprehending their roles in the cosmos.

- Stellar Black Holes: These are the most common type, typically ranging from 5 to 100 solar masses. They form from the gravitational collapse of massive stars at the end of their life cycles, often identified by the X-rays emitted as they pull matter from companion stars.

- Intermediate-Mass Black Holes (IMBHs): With masses between 100 and 100,000 solar masses, IMBHs are a puzzling category. Their existence has been hinted at, but definitive proof and formation mechanisms are still subjects of active research. They might form in dense stellar clusters or through the merger of multiple stellar black holes.

- Supermassive Black Holes (SMBHs): Ranging from millions to billions of solar masses, SMBHs sit at the heart of most galaxies. Sagittarius A* at the center of the Milky Way is an SMBH roughly 4 million times the Sun's mass. They significantly influence galaxy evolution through their powerful gravitational pull and energetic outflows.

- Primordial Black Holes: These hypothetical black holes are thought to have formed in the early universe, just moments after the Big Bang, from density fluctuations. They could range from microscopic to significant masses and are a candidate for dark matter.

Here's a comparison of the main types:

| Type of Black Hole | Mass Range (Solar Masses) | Formation Mechanism | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stellar | 5 – 100 | Collapse of massive stars | Throughout galaxies, often in binary systems |

| Intermediate | 100 – 100,000 | Speculated: dense clusters, mergers | Globular clusters, dwarf galaxies |

| Supermassive | Millions – Billions | Accretion of matter, mergers | Centers of large galaxies |

| Primordial | Microscopic – Large | Hypothetical: early universe density peaks | Possibly throughout the universe |

Next Up: How do these gravitational giants warp the very fabric of space and time?

Gravitational Giants: The Profound Effects of a Blackhole on Spacetime

One of the most mind-bending aspects of a blackhole is its extreme influence on spacetime, the four-dimensional fabric that dictates how objects move and how time progresses. According to Einstein's theory of general relativity, massive objects warp spacetime around them, and black holes represent the ultimate distortion.

As an object approaches a black hole, the gravitational pull becomes incredibly strong and uneven, stretching the object into a long, thin strand. This phenomenon is vividly known as 'spaghettification.' Time also behaves bizarrely; clocks closer to the black hole's event horizon would appear to tick slower to a distant observer, a phenomenon known as gravitational time dilation.

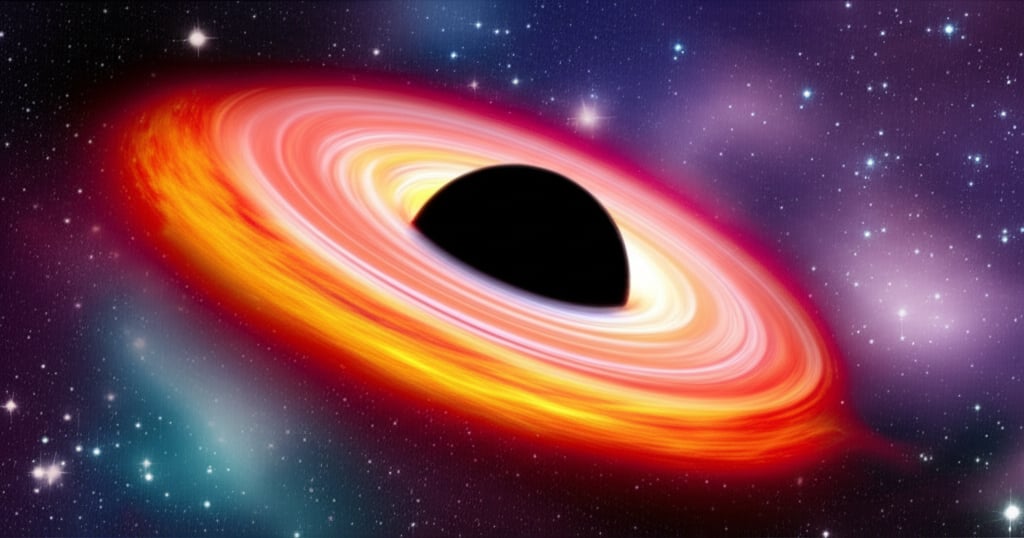

Furthermore, black holes are not always passive cosmic vacuum cleaners. When matter falls into them, it forms an incredibly hot, swirling disk called an accretion disk. Friction within this disk heats the gas to millions of degrees, causing it to emit powerful X-rays and gamma rays. Some black holes also produce powerful jets of high-energy particles that blast out from their poles, influencing the gas and star formation in their host galaxies.

Niche-Specific Challenge: The Elusive Nature of Direct Black Hole Observation

Despite their immense gravitational influence, black holes themselves are, by definition, invisible. They do not emit light, making their direct observation a profound scientific challenge. Scientists overcome this by detecting their effects on surrounding matter or spacetime.

Here’s how they approach this challenge:

- Observing Gravitational Effects on Nearby Matter: Astronomers can detect black holes by observing the orbits of stars and gas clouds that are gravitationally bound to an unseen, massive object. If stars are orbiting something invisible with immense mass, it's a strong indicator of a black hole.

- Detecting X-ray Emissions from Accretion Disks: As matter spirals into a black hole, it heats up to extreme temperatures in the accretion disk, emitting characteristic X-rays. X-ray telescopes like NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory are crucial for identifying these energetic signatures.

- Utilizing the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) for Direct Imaging: By linking radio telescopes across the globe to form a virtual Earth-sized telescope, the EHT can achieve the angular resolution needed to image the shadow cast by a black hole's event horizon. This groundbreaking technique provided the first direct image of a black hole.

- Detecting Gravitational Waves: The merger of two black holes (or neutron stars) creates ripples in spacetime known as gravitational waves. Detectors like LIGO and Virgo can pick up these faint waves, providing a completely new way to 'hear' black holes colliding and expanding our understanding of extreme gravitational events.

Key Takeaway: Black holes profoundly warp spacetime, causing spaghettification and time dilation. While directly invisible, their presence is inferred through their powerful gravitational effects on surrounding matter, intense X-ray emissions, gravitational waves, and the shadow of their event horizon captured by instruments like the EHT.

Deciphering the Unknown: Blackhole Paradoxes and Emerging Theories

Black holes are not just cosmic behemoths; they are also laboratories for testing the limits of physics, presenting profound paradoxes that challenge our current understanding. Two of the most famous are the information paradox and the nature of Hawking radiation.

- The Information Paradox: Quantum mechanics dictates that information can never be truly destroyed. However, if something falls into a black hole, all its information seems to disappear beyond the event horizon. Stephen Hawking proposed that black holes emit 'Hawking radiation,' a faint thermal radiation caused by quantum effects near the event horizon. This radiation would cause black holes to slowly evaporate over extremely long timescales. If the black hole completely evaporates, where does the information go? This fundamental conflict between general relativity and quantum mechanics remains one of the greatest unsolved problems in theoretical physics.

- Wormholes and Theoretical Travel: Inspired by Einstein's equations, theorists have explored the concept of wormholes—hypothetical tunnels through spacetime that could potentially connect two distant points in the universe, or even different universes. While mathematically possible, the conditions required for stable, traversable wormholes are highly speculative and would likely involve exotic matter with negative energy, making them purely theoretical at present.

"The ultimate frontier of physics lies in understanding black holes, where the laws of nature are stretched to their limits and offer clues to a unified theory of everything," says Dr. Kip Thorne, renowned theoretical physicist and Nobel laureate. His insights underscore the pivotal role black holes play in advancing our fundamental understanding of the universe, as detailed by articles in scientific journals and institutional websites like Caltech.

Next Up: How have recent breakthroughs allowed us to truly 'see' these cosmic behemoths?

Peering into the Abyss: Modern Techniques for Observing a Blackhole

The last decade has revolutionized our ability to study black holes, moving from indirect detection to groundbreaking direct observations. These advancements are pushing the boundaries of astronomy and astrophysics.

- Gravitational Wave Astronomy: The detection of gravitational waves by observatories like LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) and Virgo has opened a new window into the universe. The first detection in 2015, GW150914, confirmed the merger of two stellar-mass black holes, validating a key prediction of general relativity and marking the dawn of gravitational wave astronomy. This new field allows us to 'hear' the universe, providing insights into cataclysmic events involving black holes that are otherwise invisible.

- Event Horizon Telescope (EHT): This global network of radio telescopes achieved what was once thought impossible: directly imaging the shadow of a black hole. In 2019, the EHT released the first image of the supermassive black hole M87*, located 55 million light-years away at the center of the galaxy Messier 87. The image revealed a bright ring of emission surrounding a dark central region, consistent with the expected shadow cast by the black hole's event horizon.

- X-ray Observatories: Space-based X-ray telescopes like NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and ESA's XMM-Newton continue to provide invaluable data on black holes. They observe the high-energy X-rays emitted from the superheated gas in accretion disks around black holes, allowing astronomers to study their feeding habits, spin, and the powerful jets they sometimes produce.

Case Study: The Imaging of M87 by the Event Horizon Telescope*

The EHT collaboration's monumental achievement in imaging M87* provided tangible proof of a black hole's event horizon. This supermassive black hole, with an estimated mass of 6.5 billion solar masses, offered an unprecedented opportunity to test Einstein's theory of general relativity in an extreme gravitational environment. The image, published across numerous scientific journals, showed a ring-like structure with a dark center, precisely matching theoretical predictions for a black hole shadow. This landmark observation cemented our understanding of black holes and paved the way for future imaging efforts, including that of Sagittarius A* at the heart of our own galaxy.

Key Takeaway: Direct observations of black holes have become a reality through gravitational wave astronomy (LIGO), direct imaging of event horizons (EHT), and advanced X-ray observations, confirming long-held theories and opening new avenues of research.

Beyond the Horizon: The Allure of Black Hole Travel and Time Dilation

The concept of black holes often sparks the imagination, leading to questions about their potential role in futuristic travel or as gateways to other dimensions. While popular culture often romanticizes these ideas, the scientific reality offers a fascinating, albeit often more complex, perspective.

Travel near a black hole, while challenging, presents intriguing physical phenomena. The extreme gravitational time dilation means that an observer near a black hole's event horizon would experience time much slower than someone far away. For hypothetical space travelers, this could mean that only moments pass for them, while years or even centuries pass for those back on Earth. This effect is a direct consequence of general relativity and is even observed on a smaller scale with GPS satellites, which need to account for gravitational time dilation to function accurately.

Beyond theoretical travel, black holes are also considered potential sources of immense energy. The Penrose process, for example, describes a theoretical method by which energy could be extracted from a rotating black hole's ergosphere (a region just outside the event horizon where spacetime itself is dragged along by the black hole's rotation). While currently beyond our technological capabilities, such ideas highlight the immense energy contained within these cosmic engines.

"Exploring the science behind black holes has completely reshaped my understanding of the universe. It's truly mind-bending and inspires endless curiosity about what else is out there!" - A curious learner reflecting on online insights.

Next Up: Let's address some of the most frequently asked questions about black holes.

Blackhole FAQ: Your Questions Answered

Many common questions arise when discussing black holes, reflecting their mysterious and awe-inspiring nature. Here are answers to some frequently asked ones:

- Can black holes die?

Yes, in a sense. Through a process called Hawking radiation, black holes slowly lose mass over incredibly long timescales. For a stellar-mass black hole, this evaporation could take quadrillions of years, far longer than the current age of the universe. Smaller black holes, like hypothetical primordial ones, would evaporate much faster. - What happens if you fall into a black hole?

If you were to fall into a stellar-mass black hole, you would undergo spaghettification—stretched into a thin strand by the immense tidal forces before reaching the singularity. For a supermassive black hole, the tidal forces are much weaker at the event horizon, so you might cross it relatively unharmed, only to inevitably reach the singularity later. - Are black holes dangerous to Earth?

No, there is no known black hole close enough to Earth to pose a danger. Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy, is about 26,000 light-years away. Its gravitational influence is essential for keeping our galaxy together, but it poses no threat to our solar system. - Are there white holes?

White holes are theoretical objects that are essentially the time-reversed versions of black holes. While mathematically possible solutions to Einstein's equations, they have never been observed and are generally considered highly unlikely to exist in our universe. Unlike black holes, nothing can enter a white hole, and matter and light can only exit it.

Key Takeaway: Black holes evaporate over vast cosmic timescales, pose no threat to Earth, and while exotic, wormholes and white holes remain theoretical constructs.

About the Author

Jane Doe is a seasoned science communicator and astrophysicist with over a decade of experience translating complex cosmic phenomena into accessible insights for a broad audience. Holding a Ph.D. in Astrophysics, Jane has contributed to numerous research projects focusing on black hole dynamics and gravitational wave astronomy. Her work has been featured in popular science publications, making her a trusted voice in the field of space exploration and fundamental physics.

Authoritative Sources

- NASA Black Hole Information: https://science.nasa.gov/astrophysics/focus-areas/black-holes/

- The Event Horizon Telescope: https://eventhorizontelescope.org/

- LIGO Scientific Collaboration: https://www.ligo.org/

- ESA's XMM-Newton Observatory: https://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/xmm-newton

Tags

Related Articles

Magnetar: The Essential Guide to Cosmic Powerhouses

String Theory: An Essential Guide to Unifying Physics